This is a guest post from my friend Sam Davies of SamuelThomasDavies.com. Sam is an expert on human psychology and always has awesome insights on how to use habits to improve your life.

###

We begin with the best intentions.

We join a gym, and chose a workout. We might even hire a personal trainer.

But before long, life gets in the way. We make excuses, skip workouts, and before long—we completely get off track completely.

According to Statistics Brain, losing weight is the number one New Year’s resolution people make (with getting fit close behind). [1]

And yet, 25% of people abandon their New Year’s resolutions after one week, and the average person makes the same New Year’s resolution 10 separate times without achieving their desired outcome!

I should know—I was part of that statistic. The truth is I struggled to build my exercise habit for years.

I would get into a good routine and be consistent with my workouts—only to miss a day or two, lose momentum, and then give up entirely.

That is until I researched the best principles for forming an exercise habit and built myself a system that allowed me to work out consistently, gain more muscle, and get in the best shape of my life.

And in today’s article, I’ll show you how you can, too.

Step #1: Identify Your Goal (and Why)

For change to occur, you need to identify, concretely, what you want to achieve.

Be specific. “I want to work out regularly” is ambiguous. “I want to go to the gym every Monday, Wednesday and Thursday between 8:00 and 10:00 a.m.” is actionable.

It’s not enough, however, to identify what your goal is—you need to identify why you want to achieve it, too.

Why did the Wright brothers achieve the first powered, sustained and controlled airplane flight, when their competitor—Samuel Pierpont Langley—had better equipment, better funding, and better education?

Simple: they started with Why.

Ask yourself, “Why do I want to develop the habit of working out?”

Do you want to get a six-pack? Or build 20 pounds of muscle?

Your answer will often be superficial at first. That’s okay. But it probably won’t be enough to motivate you in the long-term.

Ultimately, you need a Why that will satisfy a value that’s important to you. This is known as a “core motivation”.

For example, “I want to build an exercise habit because I want to look good naked” is good, but, “I want to build an exercise habit because I want to run the Boston marathon and raise money for charity” is better.

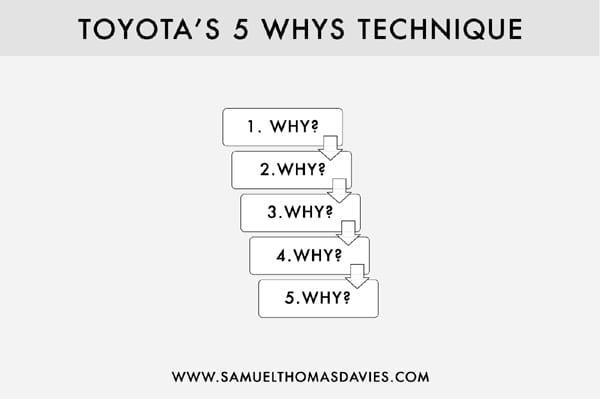

To identify your core motivation, you need to use what writer Stephen Guise calls a, “why drill.” [2]

A why drill invites you to ask yourself why you want what you want five times.

Asking why five times helps you identify your core motivation and helps you differentiate between what you think you want from what you really want (and probably need).

Example:

“I want to build an exercise habit.”

“Why?”

“Because I want to get a six-pack.”

“Why?”

“Because I want to feel good about my body.”

“Why?”

“Because I want to feel more confident.”

“Why?”

“Because I want to find my soul mate.”

“Why?”

“Because I want to settle down and start a family.”

By the third or fifth why you should have your core motivation—the real reason you want to exercise.

When you know your Why, the how makes itself available to you.

Step #2: Develop a Plan

Once you’ve identified what you want to achieve and why you want to achieve it, you need to develop a plan.

This comprises 3 steps.

- Choose a cue

- Identify a reward

- Write an implementation intention

Let’s look at each step in turn.

Choose a Cue

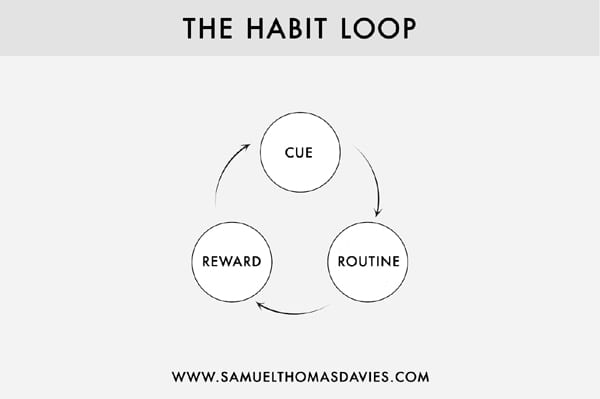

In his New York Times bestselling book, The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg explains at the core of every habit is the same neurological loop called the habit loop. [3]

The habit loop comprises 3 steps:

- Cue. This is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use.

- Routine. This can be a physical or mental or emotional behavior. In our example, going to the gym is the routine.

- Reward. This is (a) the reason you are motivated to do the behavior and (b) the way your brain can encode the pattern if it’s a repeated behavior.

An example of the habit loop in your everyday life might look like this:

- Cue. You feel bored (emotional state)

- Routine. You go to the cafeteria and order a chocolate chip cookie

- Reward. Your brain releases dopamine and you feel pleasure

According to Duhigg, there are five types of triggers:

- Location

- Time

- Emotional state

- Other people

- Immediately preceding action

In my experience, an immediately preceding action is the most reliable trigger.

Why?

Because you can use an existing habit as a trigger.

Take waking up, for example. It’s a behavior you do every day. You never need to decide whether to wake up or not—you just do it.

When I was building my gym habit, I chose to use waking up for that very reason. I woke up, picked up my gym bag and went to the gym (more on that later).

Introduce a Reward

Forgetting to introduce a reward is the most common reason people fail to build an exercise habit.

Instead, they will themselves to exercise. And as you know, willpower is a limited resource. The more we expend it on non-essential decision making—like when to go to the gym—the more likely we are to default on that behavior.

This is why creating systems is so crucial. With so much information competing for your attention, you want to conserve the little willpower you have for building better habits (at least, in the beginning).

Really, the habit is the reward, both in and of itself. But, often, that’s not enough to form a habit from the offset.

Here’s what Duhigg says about rewards:

Want to exercise more? Choose a cue, such as going to the gym as soon as you wake up, and a reward, such as a smoothie after each workout. Then think about that smoothie, or about the endorphin rush you’ll feel. Allow yourself to anticipate the reward. Eventually, that craving will make it easier to push throughout the gym doors every day.

I recommend, what I call, “reward bundling”.

This is when you combine an existing activity that’s rewarding with one that isn’t rewarding—yet.

Examples of reward bundling include:

- Listening to podcasts while you’re strength training

- Watching TV while you’re running on a treadmill

- Speaking with a friend on the phone while cycling on the bike

Reward bundling is an opportunity for you to reward yourself for doing that habit, both, during and after the activity.

Remember: rewards satisfy cravings.

Anticipate your reward, and the habit will take care of itself.

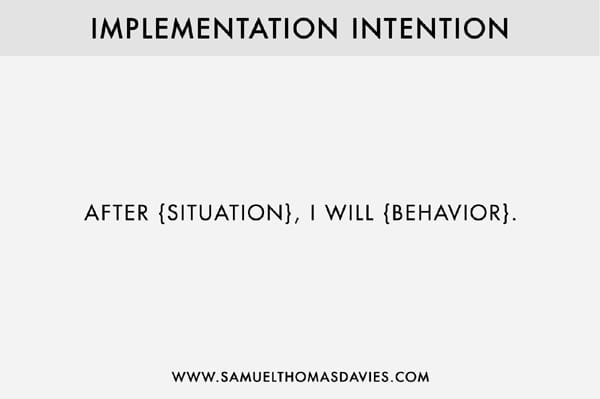

Write an Implementation Intention

Once you’ve identified a trigger and a reward, you need to put your plan into writing. Specifically, what to do and when to do it.

To do this, I recommend using what’s called an “implementation intention”.

An implementation intention is a strategy that helps you identify your goals by specifying exactly what you’re going to do and when you’re going to do it.

For example, you might write:

After I [WAKE UP], I will [PUT ON MY GYM CLOTHES].

By writing an implementation intention, you’re freeing up your need to decide what to do and when to do it, and conserving your willpower for what matters most—building the habit of working out.

Step #3: Optimize Your Environment

There’s a reason Shawn Achor finally built the habit of practicing guitar when he moved his guitar from his cupboard to the center of his living room—he simplified the behavior. [4]

In his own words:

Lowering the barrier to change by just 20 seconds was all it took to help me form a new habit.

Achor’s “20-second rule” is one of many examples of what’s known as “environment design.”

The idea is simple: by reducing the number of steps needed to do a behavior—like going to the gym—we make the behavior simpler and therefore easier to do.

One of the best examples of environment design, in an exercise context, is from Ramit Sethi.

When Ramit decided he wanted to put on muscle, he packed his bag the night before and placed his workout shoes by his bed so he’d trip over them when he woke up. This not only served as an additional trigger—it was one less barrier to overcome.

Think about how you can redesign your environment.

Can you pack your gym bag the night before? Plan your workout in advance? Chose a gym that’s closer to your home or work?

Sometimes, all it takes is one small tipping point to trigger a big breakthrough.

Step #4: Track Your Progress

Tracking your progress is crucial when building an exercise habit.

Why?

You need to know whether you’re moving closer or further away from your goal.

As travel photographer James Clear writes, “The things we measure are the things we improve.”

To track your progress, effectively, you need a metric and a method. A metric is what you’re going to track. A method is how you’re going to track it.

You might decide to track the amount of weight you lift during a workout, the number of days you go to the gym, etc. Ideally, choose a metric that is closest to your goal.

My goal was to put on more muscle. By tracking my body weight and the amount of weight I was lifting, I was able to measure if I was going up in weight and getting stronger.

One way to track your metrics is to play small, addictive games.

In his book, The Little Book of Talent, Daniel Coyle discovered that people who become experts in their field think differently about practice. They are the ones who embrace repetition and fall in love with the process. [5]

Rory McIlroy chipped golf balls into the family dryer. Warren Buffet sold chewing gum door-to-door and tried to figure out which flavor sold the best. Keith Richards tried to decipher riffs on old blues records.

The governing rule is this: if you can count it, it can be turned into a game.

For example, when I was counting calories, I saw my total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) as a “score” I needed to break. This made eating more less stressful and more enjoyable.

Count the things that matter and you’ll arrive at your goal a lot sooner that you expect.

Step #5: Focus on a Ritual Rather Than a Result

After achieving a goal, many people fall back into their old patterns

Why?

Their lives momentarily lose meaning. That very thing that they were moving toward is gone. And in its place is a void.

The truth is, the goal—losing weight, getting fit, putting on muscle—isn’t the goal at all.

The real goal is building a ritual.

A ritual of exercising. A ritual of working out. A ritual of counting calories.

A ritual you won’t want to live without once you’ve achieved your goal.

Yes, having a result in mind is important, of course, but what’s more important is building a ritual that will allow you to continue progress once you’ve accomplished what you want.

When you build a ritual of showing up and doing the work, consistently, the result becomes a natural byproduct of your hard work.

…But Remember: Exercise is a Choice

I’ll leave you with this: most people look at working out as something they have to do. But the truth is it’s something you get to do.

Ultimately: exercise is a choice.

You can choose to get into shape. You choose to feel good about yourself. You can choose to become the best version of yourself.

And you can choose to do it now.

This was a guest post from Sam Thomas Davies. Check out this blog at SamuelThomasDavies.com.

References

[1] Statistic Brain (2015) New Years Resolution Statistics, Available at http://www.statisticbrain.com/new-years-resolution-statistics/ (Accessed: 22th May 2016).

[2] Guise, S. (2013) Mini Habits: Smaller Habits, Bigger Results, USA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

[3] Duhigg, C. (2012) The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, New York: Random House.

[4] Achor, S. (2010) The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology That Fuel Success and Performance at Work, New York: Crown Business.

[5] Coyle, D. (2012) The Little Book of Talent: 52 Tips for Improving Your Skills, New York: Bantam.

Love the 5 whys!

And remember: exercise is a choice. Good point. 🙂

Great article and cool, simple images. Thanks.

Thanks Jonas – I’m glad you enjoyed it!

College students’ research paper https://seifertforgovernor.com/tips-to-writing-an-interesting-finance-research-paper-in-2020/ requirements on financial topics are often recognized as among the most difficult sections of the curriculum. Submitting a high-quality paper, however, is not an impossible endeavor.

When Ramit made the decision that he wanted to put on muscle, he prepared for his workout the night before by packing his luggage and placing his gym shoes next to his bed in such a way that he would trip over them when he woke up.

I recently utilized a finance essay writing service and was thoroughly impressed with the in-depth analysis and structure they provided. It significantly boosted my understanding of the subject.

So! These exercises are really effective not only for the legs, but also for the whole body. I also created my own exercise system that includes elements of your exercises. Leaving is not a bad thing. I have it in my book report outline https://writepaper.com/blog/book-report-outline